Intervention

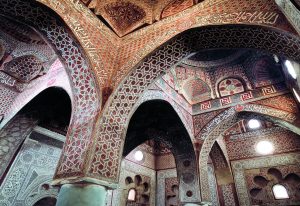

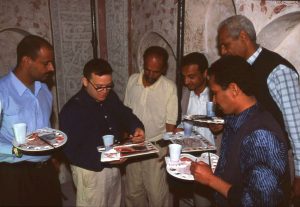

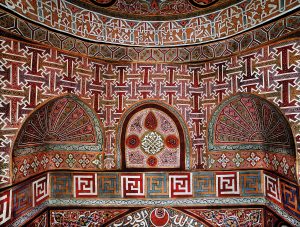

The treatment implemented on the painted surfaces and their support was intended to reinforce the materials, return them to their function, and improve the legibility of the whole and individual decorative elements. From the technical standpoint, a traditional intervention was involved, with operations such as consolidating the plasters and paint layer, surface cleaning, stuccoing lacunae, pictorial integration, and final protection.

Materials and treatment techniques were guided by the original constituent materials and the type of damage and alteration products on the surfaces.

Consolidation and protection of the paint layer

As there were raised flakes of color, the fragments were readhered to the underlying plaster through localized impregnations of Primal AC33, diluted 5-10% in water. To restore cohesion to powdery color, the areas affected were sprayed with a 3% solution of Paraloid B72 in acetone. Given the extreme fragility of the paintings in the presence of moisture, we decided – after cleaning – to supply a preventive protection over all the surfaces with the same product before consolidating the plaster. That operation would require the use of water, both to make the consolidating mixture fluid enough to penetrate at depth, and for preparatory phases using water and alcohol to clean internal areas for treatment. Moreover, this protective layer isolated the original paint layer from subsequent pictorial integration work on the paintings, and would facilitate future removal, if necessary.

Cleaning

The nature of the Amiriya paintings called for a preferential use of dry, mechanical cleaning systems, both for removing loose surface deposits, such as mud, salt efflorescences and dust, and for more stubborn ones, such as dust trapped in slightly oily layers. All the surfaces were thus initially dusted with ermine or soft bristle brushes, and the deposits were vacuumed up at the same time.This phase was followed by cleaning with Wishab sponges, but only in the areas where there were still layers of persistent dirt. The combined action of dusting with brushes and sponges made for satisfactory removal of most of the deposits, providing an even and sufficiently balanced presentation of the surfaces in all the domes not affected by deposits of lamp black and carbonated layers. For those areas, we had to use chemicals to dissolve the deposited substances and break their chemical bonds, which permitted subsequent removal.

To remove lamp black deposits, we used repeated applications of a mildly alkaline solvent mixture based on ethyl alcohol, ammonium, acetone and water in equal parts; this was left to act for a few minutes on the surface through paper tissues. Once the layer was softened, the removal or reduction was done by patting with cotton pads soaked in the same solvent.

In the lower wall areas with whitewash, it was enough to remove it mechanically with scalpels, gradually reducing the thickness until it was gone, generally softening the layer with applications of water, alcohol and acetone in equal parts. Beneath this layer, as was to be expected, the color was more consistent and lively in tone, given that the whitewash had inadvertently protected it from the environment over the years.

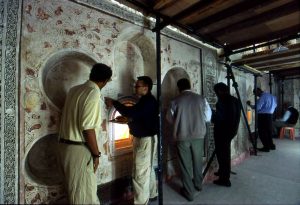

Consolidation of plaster detachments

For surface detachments between plaster layers, which were generally of limited extent, we used Primal AC33 diluted 25-50% in water.

Consolidation of detachments between the plaster and the wall support (which were sometimes quite severe) called for a consolidating material with both adhesive and filling properties so that once the mass had solidified, the lost material could be recovered. An hydraulic, pre-mixed consolidant, PLM-A, was used for this purpose.

Depending on the extent of the detachment in width and depth, the injections were done with great caution to avoid having the weight of the consolidant cause the final collapse of the plaster in areas that were already barely attached. As the work went on, supporting braces were used to hold the areas being consolidated, and work proceeded from the lower part of the detachment, gradually moving upward. Intervals of 24-48 hours were observed between one infiltration and another, to permit partial solidification of the consolidant and progressive anchorage of the surfaces.

Where there were fragments that were too detached for infiltration treatment, we applied gauze to them and detached them temporarily. The fragments were then reapplied to the wall with a mortar of lime, gypsum pozzolana and local calcareous filler. If necessary, gaps in the brick wall were filled in and wooden elements replaced if they were damaged or lost.

Stuccoing lacunae in the plaster

Large-scale stuccoing in the domes and along the walls where loss of original plaster exposed the wall support was done with a mix composed of slaked lime, hydraulic lime, gypsum, pozzolana and sifted calcareous filler, applied in two layers to a previously dampened surface, and worked at length to make sure it adhered to the masonry.

Small lacunae a few centimeters across caused by the fall of the last layer of plaster – especially if in a context that could be integrated with pictorial retouching – were stuccoed at the level of the original plaster with a gypsum mix and then retouched with watercolors.

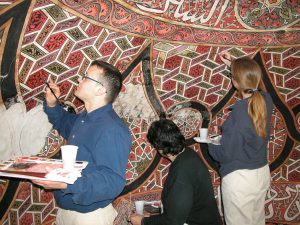

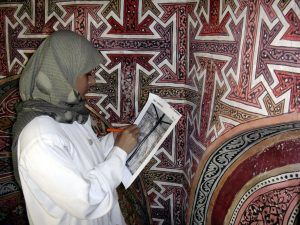

Pictorial integration: between restoration and preventive conservation

Given the extent and variety of the lacunae found, different types of integration were adopted, but all were done with watercolors. Some lacunae could be integrated by reconstructing the missing motifs, which were repetitive and therefore easy to interpret. Others could not be filled because they were too large and integration would have meant a general falsification of the paintings. Lacunae in the paint on the inscriptions were always fully reconstructed for purposes of worship.

Lacunae surrounded by well-preserved painted areas were then integrated by reconstructing the lost motif, leaving a light undertone of color so that the treated area to be easily recognized on close inspection. More extensive lacunae were treated with a ground color that blends with the general tones of the surrounding painting, thus creating a uniform plane behind the remaining colors and facilitating emergence of the forms.

Abrasions and spot losses of color were integrated with inconspicuous glazing, which re-established continuity and depth to the tones. Otherwise they were difficult to read and highly fragmentary.

The most complex recovery was that of the decorated register above the doors, where the extreme consumption of the color – throughout the room – interrupted the decoration in a disturbing way and and impeded a proper reading of the spatial relationships of the architecture. Nonetheless, the original plaster exposed did allow traces of the original drawing to emerge, together with the faded imprint of the color. Consequently, we decided to recover the drawing by heightening the tone of the traces of color with highly transparent and watery glazing, which now assists the reading of the otherwise illegible original decoration. The treatment can immediately be recognized by the pastel tones used, and permits both the reading of the original decoration and a balanced chromatic connection with the richly-colored decorations above, re-establishing the formal relationships between architecture and decorations.