Conservation condition

The Amiriya madrasa is built in an area at high risk from earthquakes, the last of which was of particular intensity in 1982 when restoration work had already begun on the building. It affected the region of Radà and Dhamar.

We cannot precisely date when the building began to decay because there are absolutely no records about its construction and history. Nonetheless, from analysing its condition it is reasonable to suppose that repeated seismic events took their toll on the building’s solidity over the centuries, gradually undermining first the external structures and decor and then the painted surfaces. The only available evidence comes to us from photographs of the building’s exterior taken in the early 1900s by Hermann Burchardt. In these, one can already see a serious state of ruin, with large cracks in the walls and a clearly obvious collapse of architectural parts and external decorative features.

The forms of alteration found on the painted surfaces can thus be briefly summarized as the combination of the following events:

- earthquakes;

- chemical and physical interaction of constituent materials with the environment;

- extreme vulnerability of the constituent materials to the action of water in all its forms;

- damage related to human frequentation and voluntary or involuntary actions on the surfaces;

- natural aging process of the original materials.

Problems related principally to the destructive action of earthquakes were found on the wall support and the plaster layers, subsequentially aggravated by heavy water infiltration from the roof and windows.

Telluric movements were responsible for the following types of damage:

- cracks and breaks in the wall structure and plaster layers, with sagging near the arches;

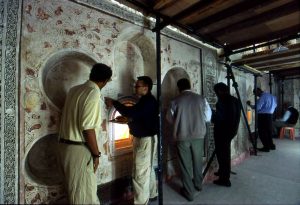

- detachments of various amounts of plaster fragments from the support; in the domes, 90% of the plaster was completely detached from the wall and about to fall;

- lack of adhesion of the plaster to the support and among preparation layers;

- lacunae (gaps) in the intonaco, particularly extensive in the domes.

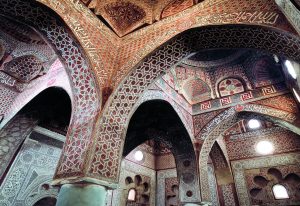

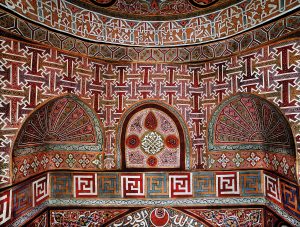

Cracks in the ceilings of the domes, which were originally done with a lime-based mortar called qudad, led to a particularly aggressive form of water infiltration afflicting the paintings, which are naturally susceptible to moisture. Veritable streams of rainwater from the roof were found in all the domes. Apart from undermining plaster stability by causing erosion in the underlying clay layer, the water had also flowed over and erased the paint layer in these areas over the course of time.

In the Amiriya madrasa paintings, the water effect involved mechanical damage due to its flow over the surfaces, as well as chemical damage from dissolution and crystallization of soluble salts in the constituent materials of the structure and plaster, and in the water itself. This problem was found principally in the domes, where the presence of water was greater and where rising currents of warm air created frequent variations in temperature. These factors caused migration and crystallization of salts on the surface, and the pressure of the crystals led to progressive deterioration of the paint layer and the thin plaster beneath it.

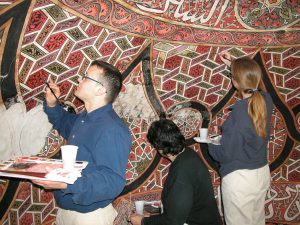

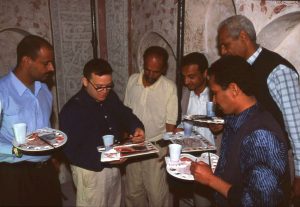

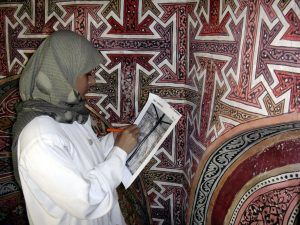

Uninterrupted public use of the hall for worship led to other kinds of damage to the lower wall surfaces.

Scratches, abrasions and even incisions in areas reached from below occurred during attempts to clean the surfaces with inappropriate tools wielded by clumsy hands. Over time, the progressive loss and disappearance of upper paint layers was probably due to dusting, of which clear traces were found.

Thick layers of whitewash, commonly used to disinfect and clean the surfaces, covered entire painted areas above the stucco decoration. Mostly thrown from below to whiten the stuccoes, this layer had also covered roughly a meter above them over the years. Oily deposits blackening the surfaces – particularly in the central dome – can be attributed to the smoke from oil lamps used to light the hall. Centuries-old layers of thickened dust, cobwebs, wind-borne atmospheric particulate and mud washed from the structure obscured all the surfaces, especially out-jutting features. All this gave the paintings a dismal gray appearance and hid the chromatic and decorative wealth of the cycle, which fortunately has now been rediscovered.