Introduction

In the busy city of Radà in north Yemen, at an altitude of 2400 meters, the prayers broadcast at peak volume from the loudspeakers of minarets all over are mixed with the deafening sounds of old cars and motorbikes, as well as generators activated when electricity is rationed. A constant roar accompanies the life of this place, enclosed by bare, hard mountains: the argumentative chatter of the men, intent on chewing their qat, contrasts with the quiet swish of the veils that completely cover the women in public; the festive chatter of the children, who play wearing rags, barefoot or with battered shoes, in the midst of trash, goats and hens scratching for food, contrasts with bursts of machine-gun fire, shot in the air as signs of celebration (or otherwise) and the metallic clanking of the chains that tie the mentally ill, who are left to wander aimlessly on the streets.

The wind carries dust, pastel-colored plastic bags, dried qat leaves and everything else in its path. Pungent smells and dirt in particular: ancient ocher dirt, the same dirt as used to build the houses. Fantastic mud-brick architecture, unique of its kind, marks the landscape in this region: in style and technique it mirrors the identity of a people holding the record of being among the poorest on the planet but among the richest in traces of the art and culture of antiquity.

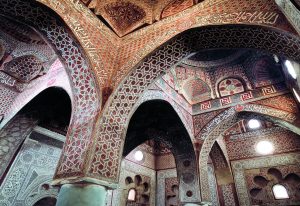

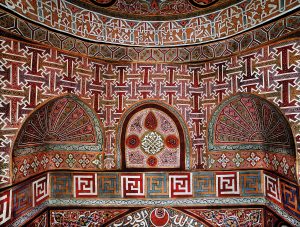

The Amiriya madrasa (1504) occupies a position of note in the city and the entire country. Among Yemeni monuments, it represents a jewel of Islamic art with its equilibrium between imposing structures and the refined detail of its decorations. At the end of the 1970s, after 500 years of abandonment, the building was close to collapse. Numerous earthquakes, together with the deterioration of the Yemeni society, far from the splendors of the flourishing years of commerce and growth of the past, faced with poverty, social and health emergencies, corruption, militarization of the state – all this had left the madrasa to its inescapable able destiny of ruin.

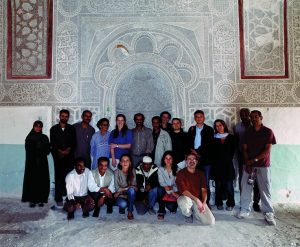

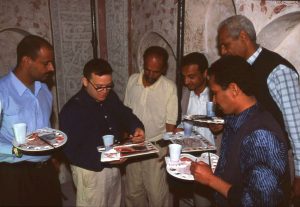

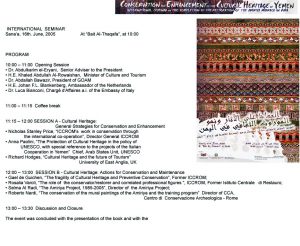

An illuminated, determined and tireless Iraqi archaeologist interrupted this dire unluckly process: Selma Al Radi. Thanks to her efforts, which led to the implementation of an all-inclusive conservation program starting in 1983, the madrasa has now returned to being the fulcrum of the city’s life, a resource of economic, social, religious and cultural development for the citizenry and an inestimable wealth for all. After twenty-two years of work, with the financial support of the governments of the Netherlands, Yemen and Italy, the Amiriya project, directed by Selma Al Radi, under the supervision of the Antiquities Department of Yemen (GOAMM), ended in 2005.

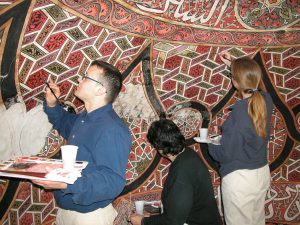

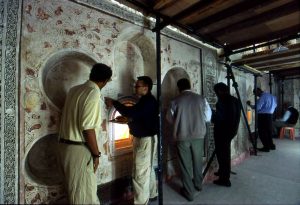

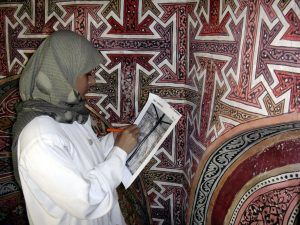

In 2007 the project received the prestigious recognition of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture. After a planning phase in 1998, the Rome-based CCA, Centro di Conservazione Archeologica, spent the period of 2003-2005 in conserving the wall paintings that decorate the prayer hall of the madrasa, as well as correlated initiatives of training and diffusion, financed by the Italian government.